Deepening Connections Through One-on-One Advisory

Following months of adaptations, adjustments, and innovations to navigate remote instruction and sustain contact with students, the Academy for Careers in Television & Film (ACTvF) continues to develop ways to maintain the closeness they developed with students virtually. Ninth grade teachers learned that one-on-one advisory and tutorial meetings were invaluable to building more intentional learning opportunities. Now that they are in person, ACTvF is seeking ways to sustain connections with students, including through empathy interviews, and individualized check-ins.

For the last 14 years, advisory at ACTvF has helped groups of students across all grades navigate the academic and social challenges they face in high school. However, the pandemic and school closures pushed ACTvF to prioritize one-on-one teacher-student meetings during advisory in order to more closely listen to individual student needs. Ninth grade advisors analyzed the content and frequency of those meetings, leading to new discoveries about their students’ learning, prompting academic adjustments. And while in-person learning is less amenable to the one-on-one supports made during remote instruction, ACTvF has continued to work on ways to sustain those innovations.

ACTvF is a Title I school in Queens serving a rich diversity of students that, as Principal Rob McCubbin notes, “is reflective of New York City.” Although the school specializes in television, film, and production, students are not required to have a portfolio to apply, and all are welcome. Teachers and staff recognize that their students bring a variety of skills to campus, and also face a number of challenges – from friend group fights to food insecurity – that invariably impact their academics. Through their advisory program, educators at ACTvF are able to look for the root of each students’ struggles, and strive to address them individually, rather than apply blanket interventions.

ACTvF strives to align advisory with students’ backgrounds, academic and social needs, and takes into account existing relationships. Advisors spend anywhere from 30% of their contracted work time supporting their group of 13 to 15 advisees. They spend this time lesson planning, conducting advisory conferences and parent outreach, and leading parent teacher conferences. Advisees meet with their advisors even before the first day of their freshmen year when the advisors help them navigate their new terrain, through their senior year. Typically, pre-pandemic, advisory consisted of group meetings during a 30-minute scheduled class time four days per week, and once every two weeks for individual check-ins. Advisory groups discuss student issues, academic or social; explore colleges, and later complete college applications; and, provide students extra support on current classwork. Teachers share advisory experiences, and collaborate with one another and a team of social workers to develop lessons that respond to student-specific needs, during weekly meetings, through their Slack channel, and in group chats. For principal McCubbin, the investment in students’ interests, needs, home life, and dreams is the key to their success.

ACTvF leaned into their tradition of listening and responding when the pandemic and school closures led to new challenges for students. In spite of bolstering Google Classrooms and providing students with laptops and WiFi, seemingly insurmountable economic pitfalls including illness and loss of life made remote instruction as they had planned it impossible. Many students either did not attend class or kept their cameras off and were unresponsive, and it was challenging to provide support because students were also not attending or communicating during advisory. In a number of cases, students were responsible for watching siblings, caring for loved ones, or supporting their family financially.

Hypothesizing that students might need more focused time with advisors, ACTvF adapted: They pared courses down to four 50-minute classes each morning followed by advisory, then an entire afternoon of asynchronous work and one-to-one office hours. Whole group advisory occurred once weekly via Google Meet, and in one-on-one sessions with advisors on the other four days, giving students the opportunity to share questions, thoughts, and concerns that they may otherwise not have shared with a group.

According to McCubbin, this one-on-one adaptation helped sustain students emotionally and academically.

To ascertain the impact this new approach had on students, ninth grade advisors began recording the frequency and duration of their meetings. Through consistent analysis of their notes compared to records of students’ course marks, attendance, and assignment completion, advisors discovered that they were spending much more time conferencing with students than before the pandemic. According to New Visions coach Jon Green, some ninth grade teachers held over 400 advisory meetings by March 2021. Yet while numerous meetings increased student engagement and provided insight into students’ lives, the advisors also discovered that they were not meeting with all students equally: Teachers mostly met with students with identified disabilities and those identified pre-pandemic as having a "very low likelihood" of reaching a 80+ GPA by the end of their freshman year. Some teachers had spent up to 25% of their total time conferencing with a single advisee. Consequently, advisors were meeting far less with other students who needed their support but were falling under the radar. In response, advisors shifted their outreach in order to maintain contact with and support all struggling students, resulting in more engagement across the board.

Thanks to their change in schedule, the new advisory approach, and one-on-one tutorial hours, teachers could more accurately assess student learning in individualized meetings. For example, Algebra instructor Gerald Lee explained that, pre-pandemic, he and other math teachers typically pushed through the curriculum to keep pace with impending Regents exams, often leaving student misconceptions and confusions unaddressed. Lee said that for ninth graders this trend is especially problematic because many enter with misunderstandings around foundational math skills, number sense, spatial reasoning, and organizational skills. Thus, moving forward too fast amounts to greater gaps in understanding that impact learning in later classes.

But through this new schedule, and with the Regents canceled during the pandemic, Lee and other math instructors were able to slow their pace and more deeply explore students’ misconceptions during class and in one-on-one tutorials. Lee tracked down as many struggling students as possible to review math concepts one-on-one, which he says translated to greater confidence working in a group and taking public risks solving equations.

As a result, math teachers discovered that students who appeared “on-track” did not have the depth of understanding teachers had expected: Students knew formulas, but did not know how to apply them flexibly. In response, they created more time for students to play with math problems, and celebrated students’ different ways of thinking. They also constructed “a culture of error,” encouraging students to take risks and make mistakes from which to learn. And while these changes meant math instructors did not cover the entire curriculum, Lee believes these approaches critically informed his and his colleagues' teaching, and will prove beneficial for students’ long term.

ACTvF’s one-on-one adjustments to advisory helped stabilize students socially, emotionally, and academically through remote instruction. ACTvF is back to in-person learning, and striving to sustain the teacher-student connections borne from one-on-one sessions. However, maintaining what both McCubbin and Lee call the “sacred space” of one-on-ones has been nearly impossible due to a shortage of space and a shift back to their previous 75-minute class schedule, which extends whole-class learning and time for students to work on their media projects. Consequently, there is less time for one-on-one conversations in a private space.

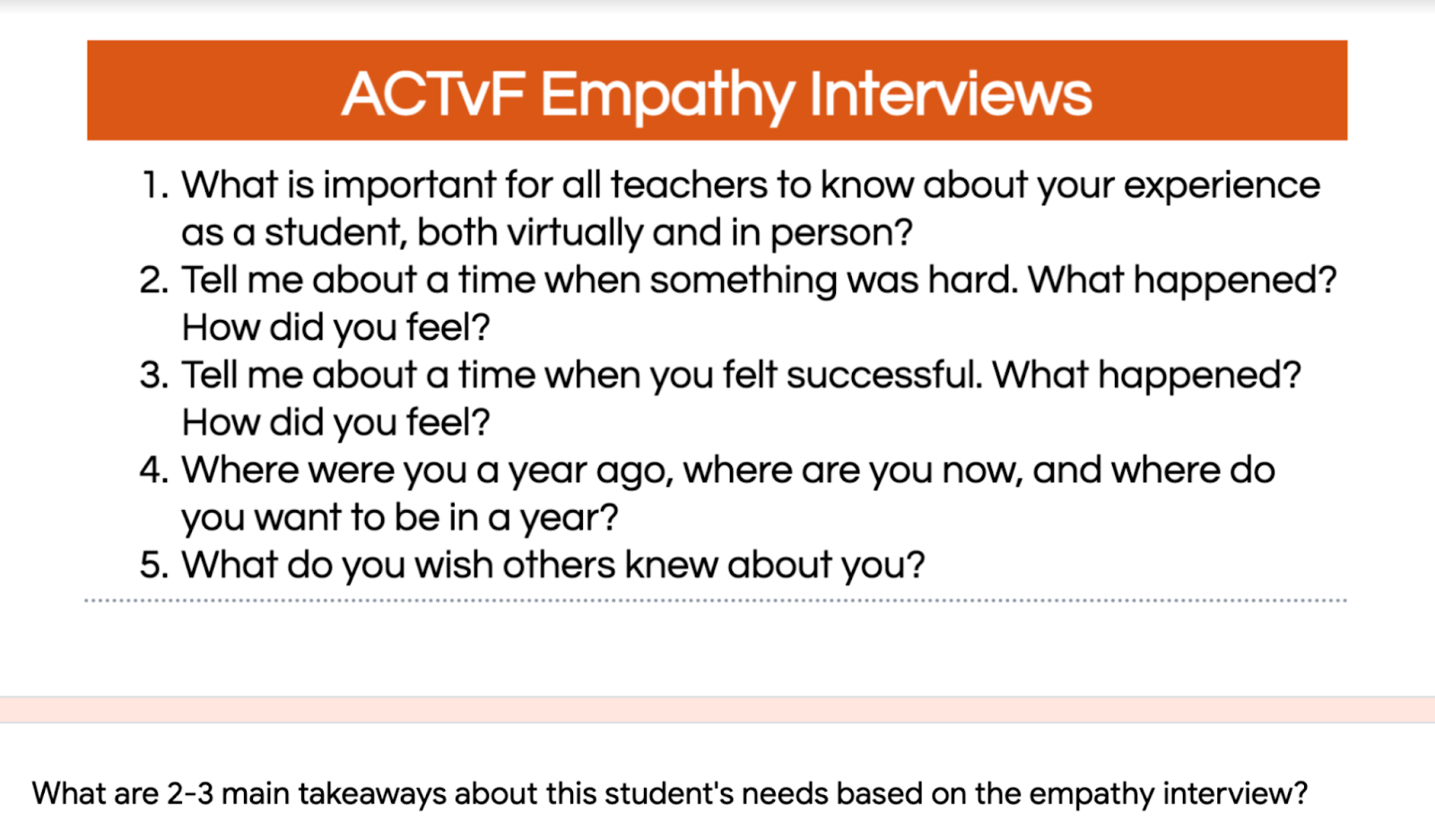

McCubbin notes that teachers nevertheless have continued exploring ways to create opportunities for those connections. For example one teacher put two chairs outside of her classroom to replicate the sense of privacy Google Meet had afforded them. But on the whole, as McCubbin pointed out, private conversations are still “happening in a room with other people now, so there is a diminished level of privacy and as hard as a teacher might try, there is also a diminished level of attention because you're going to keep an eye out for what the other kids in the room are doing.” So, taking another approach to learning about student needs, ACTvF conducted “empathy interviews” with freshmen at the start of this academic year: Advisors asked freshmen to free-write a response to three or four prompts from a menu of options. They then spent 15 to 20 minutes recording their responses in a recorded face to face interview with each student. The hope was that students would freely speak their mind, find comfort in the privacy of their self-expression, and reflect on their progress through another channel than in group advisory alone.

According to McCubbin, their responses were powerful. He sees this interview practice, though time-consuming, as necessary if the school is to sustain the very personal support needed to help students succeed.